I rose early in the morning, catching the 6:20am collectivo van to the Honduras/Guatemala border at El Florido. It was a twenty minute ride, and I passed out of Honduras and into Guatemala without any trouble. I wasn’t even asked to pay the 10 Quetzal ($1.25) bribe that I thought was standard when entering Guatemala. I got a bad exchange on my dollars and remaining lempiras for Guatemalan Quetzales, but there was no ATM anywhere, so I took what I got.

There was a bus van waiting to leave for Chiquimula,

my first stop on my way to Rio Dulce, where tomorrow I would take a boat to Livingston and then another to Puerto Barrios to cross to Punta Gorda, Belize. The helper didn’t have change for the large bill I gave him so he wrote the amount he owed me on the back of my ticket for later. The Guatemalans rival the Mexicans in their dislike for any money greater than pocket change. Give them the equivalent of a $4 bill for a $2 fare, and they will ask you if you have something smaller, and then roll their eyes in frustration when you shurg and say no.

The bus ride lasted 1.5 hours. It was crowded, but not uncomfortably so. The driver told me where to find the bus to Rio Dulce. As I approached the station, a man, as always happened, asked me where I was going, and directed me to a van. I gave him my pack, which he threw on top, and I boarded. It wasn’t until we had started moving that I heard the ayudante calling “Puerto Barrios.” Sure, I could get to Rio Dulce via this van, but I would have to change at La Ruidosa. I hadn’t asked the man if this van was ‘directo’ to Rio Dulce, and his only concern was getting me in his van and not someone else’s.

Guatemalans can pack public transport like noone else in Central America. If more people were familiar with Guatemala, the phrase might be, “packed like a bunch of Guatemalans into a bus, rather than “packed like sardines in a tin can.” I ended up wedged five to my seat, on the wheel well, against the window, next to a tiny Guatemalan woman who was very aggresive in establishing her elbow room. The ride lasted two long hours. My back hurt and my hamstrings were cramping. My watch was not my friend, so I kept it hidden away. Finally, I heard the driver say “something something Dulce.” I climbed to the front of the van, just as we were about to pull away and he told me the van stopped in front of us was going direct to Rio Dulce. I needed to start paying attention more on buses. They handed my pack down from the roof and I jumped in the next van. I was the last one on, and there were no seats. I sat on my pack, but it soon became too crowded, and I had to stand. There was about 5′ clearance, and I’m 5’10”, so I had to stand bent at the waist in a V, clutching the bar attached to the roof. We let on ten teenage schoolchildren. I couldn’t move my feet without stepping on someone, and the van door was closed, so there was no ventilation, and it was 90F degrees outside. I had no idea how long it was to Rio Dulce, but I guessed an hour.

The schoolkids got off twenty minutes later, and the packed van felt roomy by comparison, even though I still couldn’t stand up straight. The Guatemalan ayudante was wearing a polo shirt that said “Stockton Family Reunion 2008-Black to the Future.” I told myself again not to check my watch every two minutes.

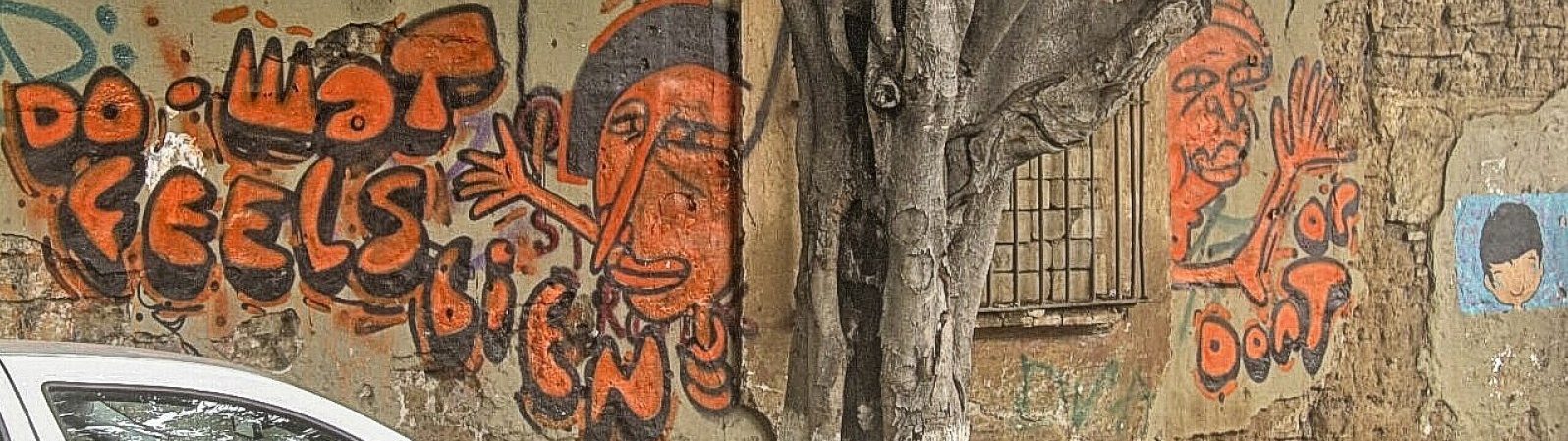

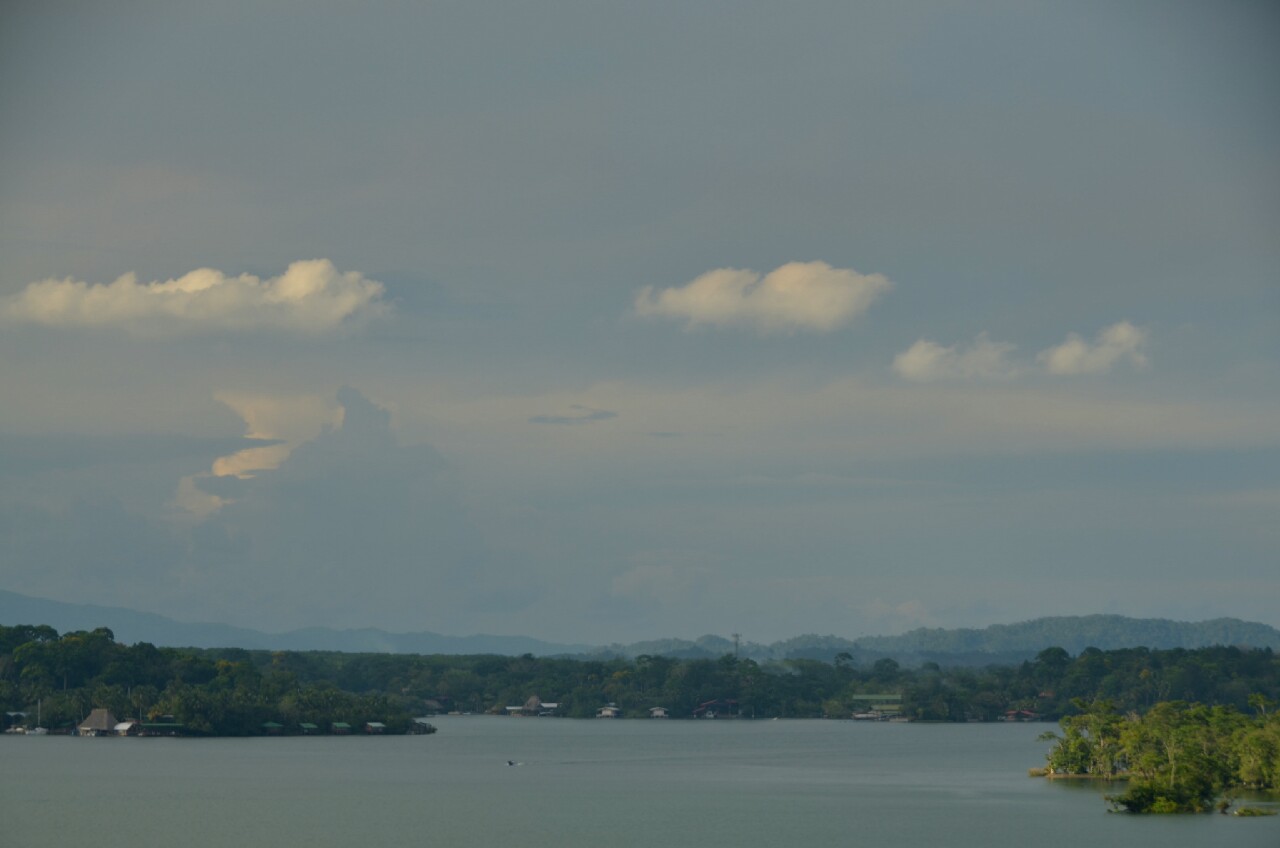

I stepped off the van in Rio Dulce. It wasn’t technically a border town, but it was the frontier to El Peten. Until the bridge was built in 1980, the only way across the river was by ferry, and the roads into the jungles of El Peten remained unpaved until after that. It still felt like you were about to cross into another country, the last stop in civilization beforing entering unknown territory.

My chosen hotel was back on the other side of the river, so I began the twenty minute walk back across.

Toward the middle, people parked their cars and motorcycles to get out and take in the view.

My van passed me just passed halfway, and the ayudante looked out, waved, and asked me why I hadn’t asked to be dropped on the other side. I told him I forgot, and he said to get in, and they drove me the rest of the way, saving me ten sweaty minutes.

The hotel was almost under the bridge.

I left my things in the room and ate street food in the park on the other side of the bridge. Two teenage boys were fishing by handline, standing waist deep in the water.

They were brothers, from Honduras. They asked me where I was from. They told me they had family in the US, but they didn’t know where. They were visiting their sister in Rio Dulce, and fishing for dinner. If they didn’t catch anything, they didn’t eat. I couldn’t tell if they were obliquely looking for a handout. Their grandfather slept in a hammock nearby. They were from San Pedro Sula, in 2012 declared the most violent city in the world, infested by gangs. I told them what I had heard, and they said yes, it was true, but they were ‘tranquilo’, peaceful, the older one told me, and made a prayer gesture sitting cross-legged. The older one tried to teach me to fish, which I did from the shore, not standing in what I assumed to be filthy, polluted water. I had no more success than they did. I gave them four of my last five cigars after they asked, having seen me smoking. I excused myself, and went back to my hotel for dinner.

The next morning, I took the 9:30am launch to Livingston, where I hoped to change the same day for Puerto Barrios and be in Belize the next.

The river journey started out boring, the river wide to the point of practically being a lake, before narrowing between high, jungly canyon walls.

We stopped at a restaurant for fifteen minutes about an hour in. There were thermal pools and bathrooms. I almost walked in on a middle aged, larger woman who hadn’t closed her stall door in the unisex bathroom, but managed to turn around before she saw me see her, I think.

Livingston felt more Caribbean than Guatemalan. I had two hours between boats, so I got lunch. If I I wasn’t in a hurry to get to Belize, I would’ve stayed a night. In travel, it can be easy to get focused on what’s next rather than what’s now.

The boat to Puerto Barrios was thirty minutes. My chosen hotel was three minutes from the dock. It was another border/port town, so I knew what to expect, and I wasn’t proved wrong. Dusty dirty and gravel streets, semi’s barrelling down the main road, people trying to make ends meet however. I was only there for a night.

I walked to a restaurant twenty minutes away for dinner. There wasn’t much near where I was staying, the comedor I had planned on eating at was closed for dinner. I stood outside the empty restaurant, watching the lightning flash over the water, debating whether to eat in this barren place or go to the market and buy a bag of doritos and a couple beers to take back to my room. On a court nearby, teenage Guatemalans were playing soccer in the spitting rain. A little boy, probably five, approached me, his eyes firmly on my pants pockets, where I imagined that he imagined my wallet full of money to be, and asked me where I was from. I told him the United States, and he asked me why I was here. I told him I was travelling, a concept I don’t think he understood. He asked if I had any money. I told him just enough for dinner. Our conversation was stilted, because I don’t speak proper Spanish, and he spoke Spanish like a five year old with missing teeth and little education. I couldn’t understand a lot of the words he was saying, but it mainly came back around to money. He told me there was no food in his house, and he was hungry. I felt I should give him something, but my money was pretty closely tallied to what I needed to eat and then buy my boat ticket to get out of Guatemala to Belize. I had no idea how to extract myself from the conversation. He asked me if I walked here, and if I was going to walk back to New York. I said no, I was taking buses. It was the kind of conversation you’d have with a five year old anywhere, random questions leading to more questions you couldn’t answer, even if you spoke the language. He didn’t have much concept of the US. He asked about the flag, and if they had buses there too, and if people rode them. He asked again if I was going to walk back. I dug in my pockets and found four quetzal coins to gve him the four quetzales. It was about fifty cents, but I knew that a bean and/or cheese pupusa cost about twenty-five cents.He invited me back to his house to eat, but that seemed like a bad idea.

I went into the empty restaurant and ordered tapado, a fish soup that is the local specialty, when I saw on the menu that the restaurant accepted credit cards. I should have googled tapado before I ordered it.

I like trying local foods, but this was just more work than I wanted my dinner to be.

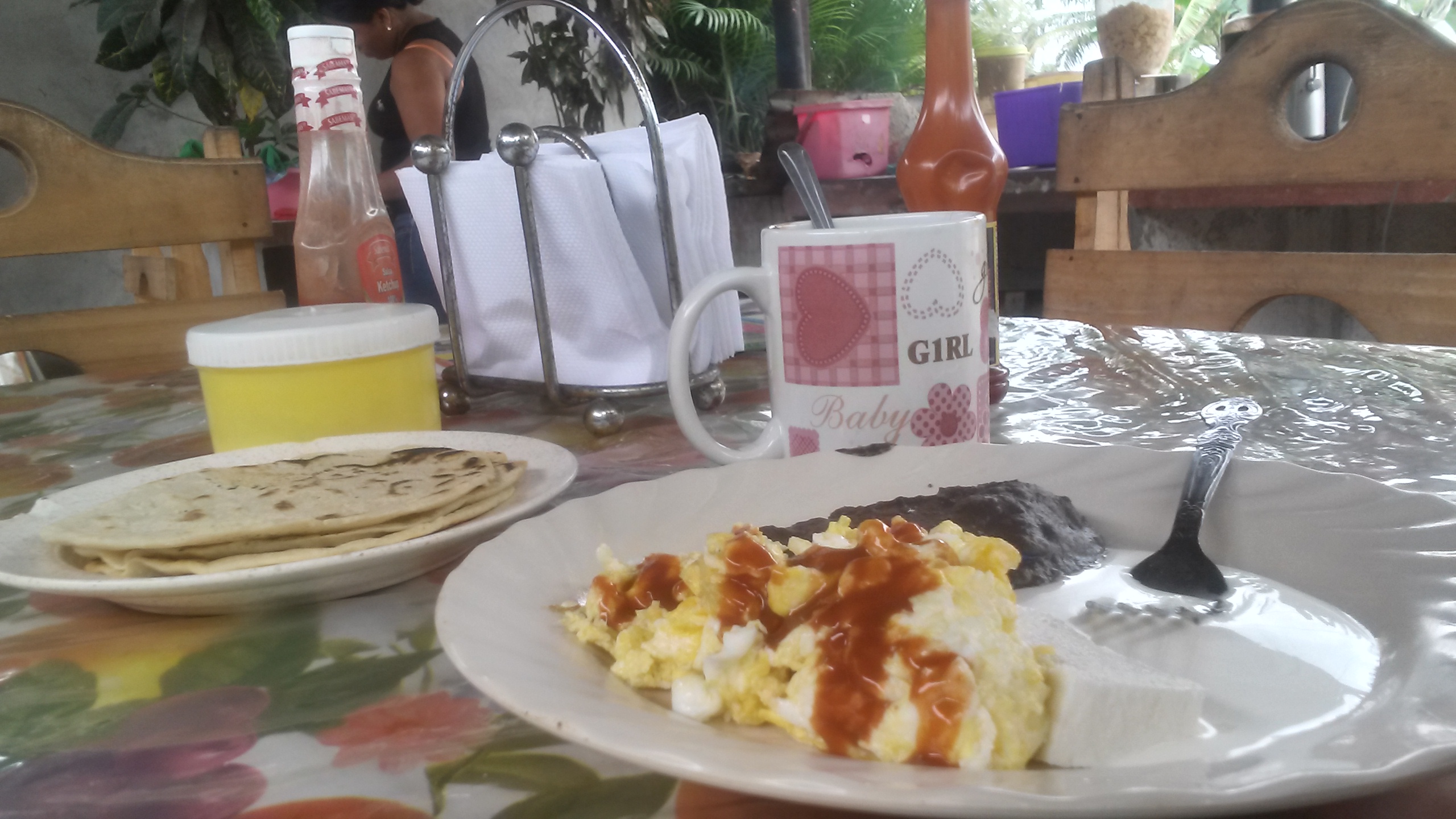

The next morning I woke to downpouring rain. I took care of my immigration stamp, which included paying $10 for the right to leave Guatemala, ate my last breakfast in Central America proper,

and headed to the pier. There was a thirty foot puddle of dirty brown water between me and the dock. There was no way but to wade across and get my feet soaked. I couldn’t take my shoes off because who knew what was under that water to cut my feet and infect me with whatever floated in the scummy mess. A man nearby laughed at my dilemna and waved for me to go ahead, so I did, ankle deep, thinking about the next seven hours I would spend with wet feet.

The boat arrived late. It wasn’t the large ferry that was sitting at the dock when I arrived, as I had hoped, but a small motorboat, with a tarp roof and no windows to protect passengers from the driving rain. Two men fastened a tarp over the luggage in the bow, causing much fretting by the German women behind me , for the safety of their Ipads as the men walked over their backpacks.

It was a cold and wet ride. I was in the first row, and as soon as we got up to speed, the tarp started whipping inches from my face. The two women from Las Vegas seated next to me helped to hold it down for the ride. We bounced over choppy waves, Rain stung our faces. I watched the shore speed by. Ninety minutes later, we were there.

The bus to Placencia was supposed to be timed to connect with the boat, but the boat schedule had changed, and we left fifteen minutes late, so I was in Punta Gorda for two hours. I went to the ATM, took out money and then went into the bank to change it for smaller bills. It was strange to speak English again. Belize may geographically be a part of Cental America, but in culture and spirit it is the Caribbean.

The bus dropped me in Independence, where I shared a taxi with the two Las Vegans to the water taxi ten minutes away in Mango Creek. By 5pm, I was checked into a hotel on the beach for $25 a night. Placencia is a sandy peninsula in southern Belize, one road,

one sidewalk

and one crescent of beach.

I had no great reason to go to Placencia. It was a just a layover on my way to Belize City, where I wanted to spend as little time as possible. It was Wednesay, and I didn’t need to be in Belize City until Friday night.

I had dinner at a sports bar nearby which was having happy hour of $1.25 beers and fifty cent wings. 80s music played and the Blackhawks/Kings game was on the tv. I sat alone, happily, amongst drunk, middle-aged white people on vacation, pretending I wasn’t a drunk, middle-aged white person on vacation. It was the kind of place that in America I wouldn’t go near, but when in Belize. Later I sat in an Adirondack chair on the beach, listening to the waves in the pitch-black cloudy night that hid the stars, until it started to rain and I had to run for my room.

The next morning, I ran on the beach, and felt not too bad considering I hadn’t run but three or four times since February, then swam in the ocean.

The water was warm and full of kelp. I had left my shoes and shirt on the beach under a palm, and I watched as a man, clearly drunk, stumbled down the beach, stopped, picked them up to check for anything he could steal, and walked on when there was nothing. A man selling wooden masks waved to me, indicating what had just happened, and I waded in and told him I saw the whole thing, and that was why I didn’t leave anything worth stealing.

I wandered the island. There was nothing to do. It wasn’t really a place to be alone, but I was happy because it just made me think of being in Caye Caulker a week from then with S.

The next morning, I walked from the water taxi to the bus stop. Six hours later I was in Belize City. My hotel was fifteen minutes from the bus station. The walk reminded me why I didn’t want to stay here. I was offered marijuana for sale four or five times, and the sellers seemed offended when I declined. The hotel was on the dirty creek that fed into the bay.

I didn’t want to go far for dinner, so I walked twenty-five yards down the street to a small lot with stands selling bacon wrapped hot dogs and tacos. I was bumped several times in a lot that wasn’t that crowded, so I kept my hand on my pocket with my wallet. A man with a filthy bandage on his hand followed me almost to the door of my hotel asking for money. My hotel sold beer at market price, so I bought two of those and ate my hot dogs and tacos.

Tomorrow, I would go to the airport, and after 61 days, I would see S again.