I operate mostly by feel when I travel. I can usually tell of a place within about an hour of walking around if it is going to be someplace I want to stay, and I could tell within an hour that I wasn’t going to be long for Jinotega. In setting it was quite similar to Matagalpa, set in a valley surrounded by mountains. The bus ride between the two is beautiful. It was hard to believe the cool, pine-scented air that rushed in through the bus windows belonged to the same country as leaden, humid air of San Carlos or Granada.

But Jinotega had suffered even worse from the fighting during the revolution and civil war than had even Matagalpa, and the ensuing poverty was still evident. It’s a working town, but in the fifteen minute walk from my bus station to my hotel, I again saw men, presumably drunk, sleeping on the sidewalks and in gutters, or standing in small groups on street corners waiting for something to do on a Tuesday morning.

I checked into my hotel, the Hotel Bosawas, for $9 a night, and was shown to my definitely $9 a night room.It was small, stuffy, hot, and smelled like toilet bowl cleaner. The only window faced into the lobby, so there was no circulation but for that provided by the fan. Normally, they rented towels to the guests, but there were out that day. It was fine, I had my own. The water worked, at least.

I went back out into the streets of Jinotega to give it a second chance.

The central park was lovely, fronted by a white-washed cathedral, terraced, with the lower part occupied by a large playground where children played and a skatepark where bmx’ers did tricks. But for it’s setting it was relatively empty, even for mid-morning Tuesday and it felt like the kind of place that if I sat for long, I would be approached for money, again and again. I found a small comedor, El Shaddai, for lunch where I got a grilled chicken thigh, rice, a small salad, a torilla and a 7Up for $3.

After eating, I decided to head to the central market to find the other bus station, where I would take the bus to Esteli. It wasn’t marked on my map, but using Google Maps, I had a general idea of where it was supposed to be.

The market was out by the highway, and was one of the nicer ones I had been to.

The street I walked down leading up to it was lined by stalls selling used shoes, strung up by the laces. The streets were open, rather than the dirty, crowded aisles of the market in Masaya or Granada. There were separate warehouses for meats, vegetables and dried goods.

I walked up and down the streets but couldn’t find the bus station. I could ask sure, but I was determined to find it myself, and not sure I’d understand the directions given anyways on these twisting streets. A man sitting on the curb tried to get my attenion saying, “listen to me, kid. Listen to me!” I just kept walking. I passed a bar full of happy people with many empty bottles of beer on their tables, and should’ve stopped in for a drink but my disappointment with Jinotega and my frustration with not being able to find the bus station made me keep walking.

I stopped at small market near my hotel and bought a beer to take back to my room while I decided what to do. I had budgeted two days for Jinotega, and after my time in Matagalpa, I was worried that wasn’t going to be enough.Now I was wondering if I’d even stay tomorrow.

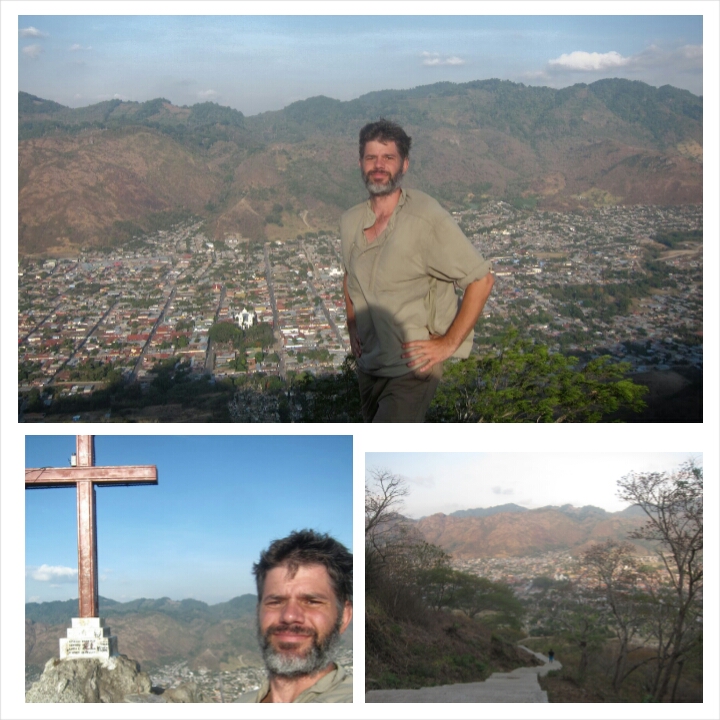

One of the things I wanted to do while I was here was hike up Cerro la Cruz, the hill dominating the town with a cross mounted at it’s peak. But it was an urban trail, starting behind the cemetary, and in my wanderings I had gone into the neighborhood nearby, and it felt a bit unsafe. Online, I had read rumors of robberies. My nerve was failing me.

I went back out in the early evening to find dinner. The only restaurant of any consequence I had seen was Soda el Tico, which was a popular buffet style place listed in my guidebook, and La Terraza, right above it, which looked expensive. Neither appealed. I walked back down to the park, to watch the families and children after work. I stood on a street corner, looking up at Cerro la Cruz. The trail was visible, and I could see a few people going up and down in the failing light of early evening. A woman walked out of the office behind me and asked me where I was from. She told me she was a lawyer, and asked how I liked Nicaragua, how long I had been there, and where I was going. When I told her that I was in Nicaragua for another week and then was going to El Salvador, she said El Salvador was dangerous. That was a common response among Nicaraguans, the same way that many people who live in the suburbs or exurbs might tell you that the city they are suburban on exurban to is dangerous, and they would never go there. She had seen me looking up at Cerro la Cruz, and asked if I was going to hike it. I said I was thinking about it, and asked if it was safe to do it alone. She said, yes, very safe, there was security. The conversation died when my Spanish failed me and her coworkers came out to head home, but she had given me something to think about.

There was a pizza truck ideally placed right next to the playground, so I bought a couple slices for a dollar and sat at one of the plastic tables to eat. As in every place I’d been, begging dogs sat at my feet, waiting for a crumb to drop or a handout. After, I wandered to find a fritanga and bought plantain maduros for dessert, which I took back to my stuffy hotel room with another beer.

In the morning, I woke up determined to get over my nerves and go up Cerro la Cruz. What’s travel without doing things that make you uncomfortable?

First I wanted to give finding the bus station another try, walking up and down every street in the market twice if need be. I found it on the one half-block I had managed to miss the day before.

I got lunch off a street cart by the park and sat down to eat, and no one bothered me. It was cold and greasy, snd I knew I would be regretting it later. Since it was now midday, I decided to hold off hiking until later, after the heat died a bit, as I had seen people doing the day before.

I started around 3:30pm. I was nervous walking up through the neighborhood and into the cemetary.

I was carrying my old camera, $4, my hotel key, that was it. Soon I came up behind two middle-aged men, one out of shape and the other in running gear.

I quickly passed the out of shape man, and then saw more and more people; teenagers coming down, women heading up in workout clothes, and about a third on the way up, and man in a brown, non-descrpt uniform with a gun tucked into his waistband. Why I assumed he was there for my security, I don’t know, but I did. I unclenched, and breathed normally again.

I understood why people hiked late in the day. Even in the morning, when the air was cooler, the sun rose opposite the peak, and you’d be walking in direct sunlight. Now, in the late afternoon, the sun had reached a point where you were shaded from it by the peak you were ascending.

At the summit, workers were putting the aluminum roof on a new viewing plaza, and there was another man, in another non-descript uniform, with another gun tucked into his waistband. I climbed hand-over-hand to the final summit where the cross was mounted, took a few pictures and enjoyed the view.

I showered and went out to find dinner. My stomach had been telling me “no more street food” for a couple days now, certainly after my greasy lunch, and I decided it was time to listen. Nothing in the Soda el Tico buffet appealed, so I headed upstairs to La Terraza. It was nice, and I got a bacon cheeseburger and fries for $3.25, the first real American type food I’d eaten since my first week in Costa Rica.

I walked it off after dinner. There was a billiards hall across the street, so I stopped for a bit and watched the men play.

A disturbed teenage boy ran down the street pretending to be a car. He made several laps while I stood there, stopping, starting, turning a imaginary steering wheel and shifting an imaginary gear shift, yelling “Beep, Beep.”

The next morning it was off to Esteli, my last stop in Nicaragua.